Analysis of Indonesia’s Current Account Deficit: Search for Fiscal Stability

Governor of the central bank of Indonesia (Bank Indonesia), Agus Martowardojo, commented on Indonesia’s troubled current account balance on Tuesday (12/08). Martowardojo said that he expects the balance to improve in 2014. Last year, the current account deficit of Southeast Asia’s largest economy reached 3.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP); a level which is generally regarded as unsustainable. This year, the deficit may ease to 3 percent of GDP. For investors the current account balance is an important matter. Why?

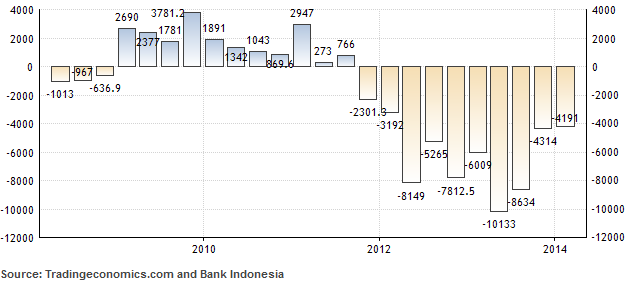

When in late May 2013 former Federal Reserve Chief Ben Bernanke started to speculate about an end to the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing program (the massive monthly USD $85 billion bond-buying program which managed to keep US interest rates low), capital outflows occurred in emerging markets. An end to quantitative easing would imply a stop to cheap US dollars flowing into riskier yet more lucrative assets in emerging economies. Those emerging economies that were hit hardest by these capital outflows were those that showed financial or fiscal instability. One indicator that investors use to assess the quality of a country’s financial make-up is the current account balance. In the case of Indonesia, investors pulled billions of US dollars out of the stock and capital markets during 2013 as looming US monetary tightening came at a time when Southeast Asia’s largest economy posted a record high current account deficit of USD $10.1 billion, or 4.4 percent of GDP, in the second quarter of 2013. This then resulted in sharp rupiah depreciation (Indonesia’s currency fell more than 25 percent against the US dollar during 2013) and a tumbling benchmark stock index (Jakarta Composite Index).

Why is the current account balance important?

A current account balance, one of the two main components of the balance of payments (the other being the capital account), is the difference between a country’s savings and its investment. It is the sum of the balance of trade (export of goods and services minus imports), net income from abroad and net current transfers. Therefore, when a country posts a current account deficit it means that the country is a net borrower from the rest of the world. The country thus needs capital or financial flows to finance this deficit.

However, a current account deficit is not necessarily bad. Similar to a company’s negative cash flow from operations, it can be positive provided that the funds are used for productive investment purposes (which result in future revenue streams). For example, industrial development or infrastructure development. However, when the deficit is merely used for consumption then it causes a structural imbalance as it generates no future revenue streams.

What Causes the Current Account Deficit in Indonesia?

When we take a look at the cause of Indonesia’s current account deficit, then we see that the main problem lies in the deficit in the oil and gas sector which - by far - exceeds the country’s trade surplus in the non-oil and gas sector. Indonesia’s oil and gas trade deficit is basically caused by two reasons: domestic oil output has been in a state of decline for almost two decades due to a lack of investments and exploration in combination with maturing oil fields (thus becoming a net oil importer and forced to terminate its long-term membership in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, OPEC) and, secondly, domestic fuel consumption has risen sharply in recent years amid solid economic growth and generous government fuel subsidies.

Domestic fuel consumption in Indonesia rose to 1.6 million barrels of oil per day (bpd) in 2013, whereas total domestic crude oil production only reached 826,000 bpd in the same year. Since 2006, the country has not been able to produce 1 million bpd and it is unlikely that Indonesia will meet this year’s revised oil lifting target of 818,000 bpd, set in the Revised 2014 State Budget (APBN-P 2014), as the country was only able to produce 797,000 bpd in the first half of 2014. This means that oil demand has to be met through expensive oil imports. Recently, Deputy Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Susilo Siswoutomo said Indonesia’s petroleum product imports averaged about 500,000 bpd in 2013. He added that the figure may rise to 600,000-660,000 bpd in 2014 provided that no government intervention takes place. Oil consultancy company Wood Mackenzie stated that Indonesia is well on its way to replace the United States as the world's largest oil importer by 2018.

A major concern is that the Indonesian government fuels domestic oil demand by providing generous fuel subsidies. In Indonesia’s revised 2014 State Budget (APBN-P 2014), IDR 392.1 trillion (roughly USD $33.2 billion) has been allocated to energy subsidies. This involves IDR 285 trillion for fuel subsidies and IDR 107.1 trillion for electricity subsidies, implying that 15.3 percent of total government spending (based on the 2014 state budget) is allocated to energy subsidies. Although aimed at supporting the poorer segments of Indonesian society, it is mostly the middle class segment that benefits from these fuel subsidies. Reducing energy subsidies is, however, problematic as it implies social and political risks. It will cause demonstrations and can push a large portion of Indonesians who are clustered just above the poverty line (back) into poverty as inflation will accelerate steeply (as we saw after the government increased prices of subsidized fuels by an average of 33 percent in June 2013).

It is important for the Indonesian government (particularly for the new Joko Widodo-led government which will be inaugurated in October 2014) to change this structural deficit by improving the country’s investment climate to attract investments in oil exploration while trying to curb domestic fuel demand by reducing massive fuel subsidies. As noted above, when funds generated through the current account deficit are used for consumption (in this case oil consumption by private individuals) then these funds disappear but the debt remains. Therefore, the country needs to direct these funds (including the money currently allocated to fuel subsidies) to long-term productive investments such as industrial development (which absorbs labour) and infrastructure (to make the investment climate more attractive and reduce high logistics costs), but also to education and healthcare.

Earlier this year, Fitch Ratings said that it expects Indonesia’s current account deficit to ease to USD $27.4 billion, or 3.1 percent of the country’s GDP, in 2014. This would mean an improvement from the deficit in 2013 but with further fuel subsidy reductions the figure should be in the range of 1.8 to 2.3 percent of GDP. With the implementation of the ban on exports of unprocessed minerals (introduced in January 2014) there has been more pressure on the country’s trade balance. However, this policy should result in higher future revenue streams due to added-value exports.

Indonesia Current Account Balance (in USD million):