Analysis of Indonesia's Current Account Deficit: the Structural Oil Problem

Fitch Ratings, one of the three major global credit rating agencies, estimates that Indonesia's current account deficit will reach USD $27.4 billion, equivalent to 3.1 percent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014. As such, Fitch Ratings' forecast is more pessimistic than forecasts presented by both Indonesia's central bank (Bank Indonesia) and government. Both these institutions expect to curb the current account deficit below the three percent of GDP mark (a sustainable level). Global investors continue to carefully monitor the deficit.

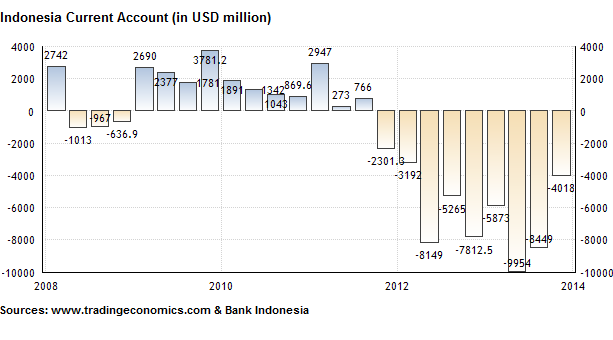

The current account deficit of Indonesia, which reached a record high of USD $9.9 billion (4.4 percent of GDP) in the second quarter of 2013, was one of the main concerns of international investors. Amid a period of high global uncertainty due to the looming end of the Federal Reserve's USD $85 billion per month bond-buying program (quantitative easing), investors pulled billions of US dollars out from emerging markets between May 2013 (when Chairman Ben Bernanke started to speculate about an end to the quantitative easing program) and December 2013 (when tapering was finally announced). Particularly those emerging markets that showed several financial weaknesses fell victim to large capital outflows.

Indonesia was one of these fragile economies due to its widening current account deficit and accelerated inflation (reaching almost nine percent year-on-year in the fall of 2013 after the government increased prices of subsidized fuels in mid-2013). Large capital outflows caused a plunging stock market as well as sharp rupiah depreciation. The Indonesian rupiah was one of the worst performing Asian currencies of 2013, depreciating over 21 percent against the US dollar.

Alarm bells rung and the Indonesian government and central bank started to implement various measures to safeguard financial stability. Firstly, Bank Indonesia raised its benchmark interest rate (BI rate) gradually between June and November 2013 from 5.75 percent to 7.50 percent in order to combat high inflation and support the rupiah exchange rate. Meanwhile, the government implemented two economic reform packages in the last quarter of 2013, aimed at boosting exports while limiting imports (mainly through taxes).

Results of government and central bank efforts were promising. After the record high current account deficit in the second quarter of 2013, it began to ease to USD $8.4 billion in the third quarter (3.8 percent of GDP), and to USD $4.0 billion (1.98 percent of GDP) in the last quarter of 2013. Sharp rupiah depreciation also brought a positive effect because it made Indonesian export products more competitive on the international market. Lastly, commodity prices somewhat improved toward the end of 2013. Meanwhile, inflation eased from 8.38 percent (yoy) at the end of December 2013 to 7.75 percent (yoy) in February 2014, while the rupiah exchange rate has been one of the best performing Asian currencies against the US dollar in 2014 (appreciating more than six percent against the greenback).

However, despite the improving trade balance, Indonesia has a more structural problem in terms of trade. The trade deficit in the oil and gas sector - by far - exceeds the trade surplus in the non-oil and gas sector. This is caused by Indonesians' huge demand for fuels amid a rapidly growing economy (expanding around six percent per year) and also fueled by government policy as the government continues to subsidize a large portion of the fuel price. As domestic oil production of Indonesia has been in a state of decline for over a decade (and the end of this decline is still not in sight because investments in oil exploration remain troublesome), it results in increasingly expensive oil imports (despite last year's higher fuel prices).

When discussing Indonesia's current account deficit or trade balance, we should also remember the influence of the country's recently introduced (12/01/14) ban on exports of unprocessed minerals. Through this ban, the government aims to increase revenues from minerals by stimulating value-added processing industries. As in the case of Indonesia, these processing facilities (smelters) still need to be build, it will result in a temporary slowdown of exports in the next couple of years, thus negatively affecting Indonesia's trade balance. Currently, commodities - particularly raw ones - account for around 60 percent of Indonesia's total exports.

Interestingly, in December 2013, Indonesia had posted an unexpectedly large monthly trade surplus of USD $1.52 billion because miners increased exports of unprocessed minerals as they wanted to export as much of raw material as possible ahead of the export ban in January 2014. This helped to ease the current account deficit in the fourth quarter of 2013, but also inflicted some false optimism that Indonesia's trade balance was healthy again. January 2014 trade data showed that Indonesia's trade balance slipped back into deficit (USD $430.6 million) as mineral ore exports fell over 70 percent (month-to-month) after the ban was implemented.

This also means that Indonesia's trade deficit and current account deficit are most likely to continue for the next couple of years. Indonesia can only hope that global demand and commodity prices will increase sharply soon to revive the 2000s commodities boom. There is one policy change, though, that can seriously improve Indonesia's trade balance: reduce fuel subsidies further (as these only distort the economy) and spend those available funds on infrastructure development as well as on social welfare programs to offset the impact of temporary high inflation on poorer segments of society. In the 2014 State Budget, the government allocated IDR 211 trillion (USD $18.3 billion) for fuel subsidies, but this will probably swell to around IDR 250 trillion due to continued robust demand (domestic car sales in Indonesia have hit a series of consecutive record highs in recent years) and rupiah depreciation. These funds should be spent more productively. However, history also teaches us that such a policy change does not come without political risks and resistance as it will trigger massive demonstrations and political backstabbing by some political parties.

Bahas

Silakan login atau berlangganan untuk mengomentari kolom ini